Why I Am Not a Liberal (Or a Conservative)

"Neurodiversity" needs to mean divergences in ideas, not just brain structure

The title of this post refers to a recent piece in the New York Times by David Brooks, “Why I Am Not a Liberal.” Brooks says that even though he finds a lot wrong with the MAGA movement and its adjacent offshoots (i.e. MAHA and whatever the hell a groyper is), he can’t bring himself to support the Democratic party because 1) he doesn’t want to feel straitjacketed by labeling himself and being coerced into supporting the full agenda of a party; and 2) the Democrats are in the process of allowing their own fringes to take over and swallow them whole.

Case in point, the centrist-ish Democratic NY governor Kathy Hochul lending an asterisk-laden endorsement (or what feels like a capitulation) to the unapologetically socialist mayoral candidate Zohran Mandami, whose ascendancy to the post in November’s election appears to be all but a foregone conclusion. Just like how the “establishment” GOP made way for Trump, now the AOC (Anarchists or Communists) wing is ascendant in the Democrats. Yeats’ fourth turning continues apace; things keep falling apart because the center cannot hold.

I think about this because of a Substack article that came across my feed asking why is there a backlash to the neurodiversity movement. In it, the author contends that part of this is a feeling by those who struggle with “divergencies” like autism/ADHD/etc. feeling unrepresented by a movement that touts purported positives of these conditions, while eliding the negatives or blaming “societal structures” for those struggles, rather than deficiencies about the condition itself. The author says that what needs to be done is to address those concerns by listening to critics and engaging with them. So I commented there about my concerns and questions as a member of the community and was promptly blocked.

So much for embracing divergent minds.

One of the concerns that I raised was how neurodiversity has become — or perhaps was always — left-coded, in that it places the sole blame for the struggles of the “divergent” upon capitalism in and of itself. That it cannot claim to be fully representative if it insists upon alienating people who do not subscribe to socialist economics or believe in radical reforms or progressive omnicause issues like the Middle East or the gender identity movement. Say what you will about Charlie Kirk (plenty of people already have) but his position was that people across the aisle need to actually have debates and discussions about issues rather than just shutting people down for disagreeing with them. Unfortunately the result was that someone who disagreed with him shut him down once and for all.

Another concern I raised is about the radicalization I see taking place in so-called “neuro-affirmative spaces” online. The kind of rhetoric calling for RFK Jr. to meet the fate of his father (“where’s Sirhan Sirhan when you really need him”), or that Simon Baron-Cohen (who is Jewish) be called to a Nuremberg court for crimes against humanity, is nothing less than appalling. Freddie de Boer commented on the piece as well, and he wrote on his Substack some time ago about a conference of autism researchers at Harvard, whose dialogue was loudly disrupted and eventually had to be cancelled because a group of “autism self-advocates” had made it untenable for the discussion to continue. “Nothing about us, without us,” says the credo of the movement. But there is little room made for those of “us” who disagree, or who simply wish to listen to or read a “divergent” point of view.

These kinds of outbursts are among the reasons why I, a millennial who cast her first presidential vote in 2004 for John Kerry, followed by Barack Obama in 2008, found myself increasingly alienated by, and unwelcome in, the purportedly inclusive blue tent.1 But nor am I a diehard for Trump either. I’m not even registered with any party despite living in a hardcore blue state. I count myself among the exponentially growing ranks of the registered independents and politically homeless. But I have found that there is more room for discussion among the ostensibly right-coded or conservative realm, than there has been on the nominal left. “Neurodivergence” itself has become vacuumed into the mess that is the progressive omnicause, and the movement risks alienating even further those who might find themselves in even partial agreement with its general aims of making the world more helpful for people with these diagnoses, but who aren’t on board with gender ideology or don’t really care about the Middle East. Autism and ADHD has nothing to do with the endless mire in the desert that has been going on since time immemorial, and “Neurodivergent Queers for Palestine” makes no sense whatsoever. Yet if you point this out rather than shut up and just march as directed, you’re a Nazi who supports Trump and genocide. The Nazis aren’t the ones calling Netanyahu “Hitler,” or Simon Baron-Cohen “Joseph Mengele.” The Nazis are (((those people))). How can I align myself with this?

Recently, another article came to my attention that I think is worth reading by those who wish to actually listen to and engage with skeptical or heterodox voices in the “neurodivergent” community who have unfortunately been shouted down by the loudest and arguably most unrepresentative on the issue. The first is by TV journalist Leland Vittert, writing in the Wall Street Journal this weekend about the struggles he faced while growing up, leading to a diagnosis as an adult in his late forties. He writes with great candor about the bullying he faced in school, from both his classmates and his teachers, and the distress that it caused his parents, especially his mother:

Growing up, I didn’t understand why I was so different from other kids and why making friends was so hard. When I was in fifth grade, the gym teacher would put me with the girls to protect me from the boys. In eighth grade, an art teacher said to me in front of the entire class, “If my dog was as ugly as you I would shave its ass and make it walk backward.”

I spent a lot of time in the principal’s office, either because I was acting out or because I was getting bullied—oftentimes both. My parents were often there too. During one meeting, my mother remembers looking down, surprised and appalled to see that she had shredded her empty Styrofoam cup into a thousand pieces.

Wow. A teacher said those things to him! And his mother was overwhelmed because she didn’t know how to help her son. Can anyone really argue that Leland, his parents, or anyone else facing that kind of torture, is a bad person for wanting to not go through this? Or not wanting to have their own children, or anyone else’s children, suffer the same thing throughout the course of their lives?

Vittert has a new memoir, Born Lucky, that I think will offer a meaningful contribution to the discussion, if people choose to listen to it. He waxes fondly about his father who taught him how to survive in a world where he was going to be a target if he was unable to stand up for himself. The most important takeaway from his father’s advice, he says, was “the world isn’t going to change for you.”

That, I think, is the takeaway that the neurodiversity movement needs to accept. Capitalism is not going anywhere; people need money to survive; work gives people purpose (and money to survive); employers and schools aren’t going to adjust their culture, hiring practices, or teaching techniques to be more accommodating, because Upton Sinclair’s law of cynical self-interest comes into play: it is difficult (or impossible) to get people to understand something when their salary depends on not understanding it.2

Vittert is a pragmatist. He is unequivocal in his assertion that autism is a health concern, not an “identity.” But he’s also not a cheerleader for RFK Jr.:

I grew up with autism, and it was hell. Understanding why autism diagnoses have skyrocketed in the U.S. in recent decades should be one of the biggest scientific questions of our time. … A condition that affects millions of children and families is too important, however, to become just another political football. Kennedy may be the wrong messenger, but understanding autism and how to prevent and treat it couldn’t be more urgent.

[I]f my wife was pregnant and I could check a box to decide whether my child would have autism or not, I would check “no” without hesitation. Who wouldn’t?

Kennedy’s history of conspiracy theories makes his search for the causes of autism easy to dismiss. But the political establishment shouldn’t prefer scoring points against the Trump administration to admitting we urgently need new research on the subject.

I don’t want to see another generation of kids face the same problems I did, or another generation of parents who are angry and frustrated that science can do so little for their children.

Too important to become another political football. Too important to allow scoring points against the administration to allow another generation of kids and parents to suffer the same problems as he and so many else have.

That doesn’t sound like Nazi rhetoric to me. That sounds like a thoughtful and empathetic person who clearly cares about other people in the same boat.

And yet, simply virtue of where it was published, Vittert’s article proves that unfortunately, this condition has already become another political football. The WSJ is a Rupert Murdoch outlet; his book is being published by a subsidiary of News Corporation, and Vittert had previously been a correspondent for Fox News. He is now at News Nation, a centrist network which critics call “Fox lite.” I’ve yet to see anything from his perspective printed in the NY Times, Washington Post, CNN or any other legacy media outlets that lean towards a more liberal/Democrat-aligned positioning plank. And it shouldn’t be this way.

Vittert is part of “the community.” So is Freddie de Boer, although his diagnosis is manic-depressive/bipolar disorder and not autism/Asperger’s/ADHD. But he hasn’t had much success getting his pieces critical of the neurodiversity movement published in the NY Times either. I’m still a neophyte, yet I doubt I ever will. But they did print a college professor who was diagnosed as an adult and whose condition doesn’t seem to have hindered his professional progress or standing in life. Vittert became successful in spite of his diagnosis rather than because of it, and not without vigorous, almost boot camp-like training by his working-class father. Surrounding those outlier success stories are countless others (like myself) leading lives of quiet desperation. Is that solely down to “capitalism”? Maybe, maybe not, but since capitalism isn’t going anywhere, I still feel the goal of medicine should be to help those struggling adapt better to the expectations and demands of modern life. If medication or some other treatment is developed, and you don’t want to use it, you don’t have to. But please don’t block people who would if they could, because you feel it will throw a spanner in the works of a reform movement. Maybe they don’t have the energy to be reformers because of the limitations of their disorder. So preventing them from getting the help they need, or shaming them for wanting that kind of help, is actually undermining the goals you wish your reform movement to achieve.

Movements need critical voices from within so that they don’t end up alienating potential allies or those who the movement says it wants to help. Blocking people, calling them fascists or traitors to the cause, let alone wishing (or threatening) death on people, is not only not helpful but harmful (and in some cases illegal). It is possible to be a critical dissenter and not a saboteur. I myself appreciated the feedback I have received from other users, and am embarking on an imperfect quest to be more nuanced and compassionate, even towards myself. But that doesn’t necessarily mean giving up on what I believe in, what my lived experience has taught me over the years. I simply can’t join the ranks of those who full-on embrace “neurodiversity” as a “movement for radical change,” without feeling like I have walked away from Omelas. For every Elon Musk and Greta Thunberg, there are kids like Jill Escher’s, and people like the agonized anons on Reddit who were called “gifted” as children and compared to rocket scientists, yet who live on welfare benefits or are homeless today because the immutable realities of the job market exclude them, so they consider their “gifts” to be a curse. I have no reason to believe that the realities of the economy are anything but immutable. I can’t agree more with this piece on why the interview process needs to be more flexible, and how it could help everyone, not just the “divergent.” But do I think this will happen? No. Just because something should change doesn’t mean it will. And in fact, the mere reason that it could potentially help the “divergent” is, sadly, why I don’t think it will happen. Perhaps I’m wrong; I’d love to be. But I just don’t see it. Faced with that harsh reality, that the laws of markets are as much a feature rather than a bug as the laws of gravity and motion, plan B seems to be the only route to go: the individual should be helped to adapt to his or her environment, because the environment will not change to adapt to, or include, him or her. The world is a business, Mr. Beale. It always will be.

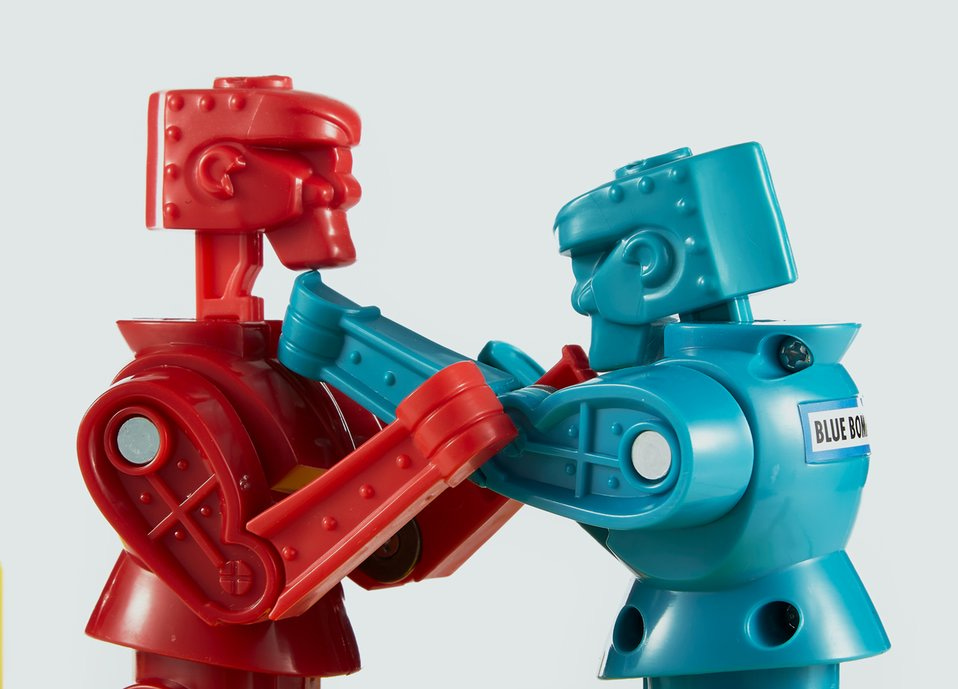

I started this Substack in hopes that people of divergent minds could defy the double-empathy conundrum, and start talking to one another instead of past them, silencing them, or shouting them down. (Let alone shooting them down.) I know that I will make mistakes as I go along; I’m only human after all. But I have my experience, and others have theirs. Neither one is more or less “valid” than the other, but at the same time, everyone is entitled to their own opinion but not their own set of facts. That said, we can’t keep pigeon-holing ourselves or one another, and we can’t keep applying, well, so many labels identifying who and/or what to avoid. We all need to stop policing dissent as “betrayal.” We need to stop fighting like red and blue robots programmed with an agenda. If we want to defy the stereotype of black-or-white thinking, we need to embrace opinion, viewpoint, and personal perspective as, well, a “spectrum” in and of itself.

We need to stop thinking in terms of this guy here and that guy there.

To paraphrase an old song: there ain’t no good guy; there ain’t no bad guy; there’s only you, and me, and it’s okay to disagree. Nothing about us, without “us.”

I also wrote that I found it interesting that Obama had at one point hired both RFK Jr. and Ari Ne’eman (founder of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network) for administration positions. RFK Jr. left, and so did I, because the Ari Ne’eman perspective won out in the Democratic party. But RFK Jr.’s fandom did not emerge out of nowhere: it emerged arguably because the Democrats had made it clear those who did not hold the ASAN’s perspective (autism is a normal aspect of human diversity, not a disorder that should be treated or cured) would not be heard or represented in their ranks. Desperate people will cling to any port in a storm when crying out for help is labeled as “hate speech.”

Sinclair was a socialist as is de Boer, but at the same time both realize(d) that they were up against insurmountable realities of human nature and “the way things are as they are.” Their belief that society would be improved by a system of distributive economics doesn’t seem to have guided them into seeing the world through rose-colored glasses, let alone turning their backs on those who don’t see the world through their views at all.